A global network of researchers led by Kerry M Stokes Chair of Child Health, Professor Pete Gething, is working to help support informed decision-making for malaria control at international, regional and national scales. Together, they are helping countries most affected by deadly malaria use their limited resources for maximum impact.

For just over a decade, between 2005 and 2017, global progress against malaria was improving year-on-year. Around 2018, for complex reasons, the gains stopped coming and – in some places – cases even started to increase again.

In response to this faltering progress, in late 2019 the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an initiative called High Burden to High Impact — a multi-faceted approach focused on the ten countries in Africa (plus India, with its own special set of circumstances) that collectively contribute around 85 per cent of the world’s malaria deaths and disease.

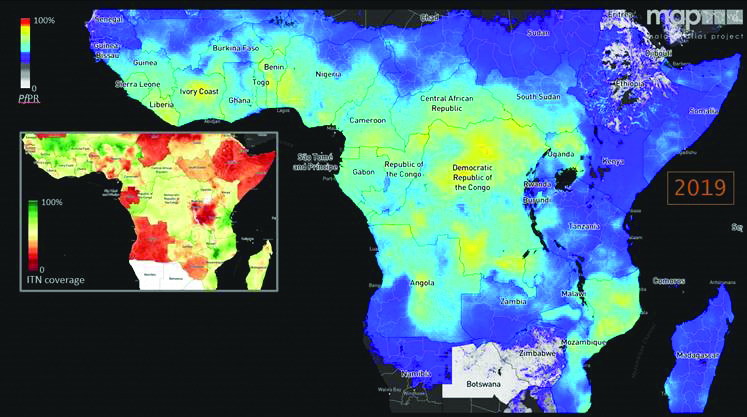

International malaria expert Professor Pete Gething and his team were already generating maps of malaria risk on a global scale for the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP), on behalf of international policymakers like WHO and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The new WHO focus meant a pivot to also cater to a different set of stakeholders: individual countries who need support for their day-to-day, month-to-month operational decisions.

That pivot has translated into sophisticated modelling highly tailored to the needs of each country. Using this modelling, Professor Gething and his MAP team are producing cutting edge statistics along with incredibly detailed and bespoke characterisations of what a country’s — and sometimes even a province’s — malaria problem really looks like.

The resulting risk maps – much more detailed than any the MAP team produce on a global level – are

co-developed with governments to help them implement the measures most suited to their country’s circumstances.

Professor Gething said reducing transmission and saving as many lives as possible was a balancing act of finite budget and resources, so it was vital that countries had information pertinent to their own conditions in order to make the best decisions on intervention tools. Potential measures include bed nets for people to sleep underneath, spraying houses and other buildings with insecticide to reduce mosquitoes, and providing access to healthcare so people can go to a clinic to get anti-malarial medication.

“We’re building relationships with these countries; working closely with them to understand what they need, what data they have,” Professor Gething said.

The team gathers data from three main sources: survey results from door-knocking with detailed questionnaires in selected villages; administrative data from medical clinics, including the number of diagnosed cases and distribution of interventions; and environmental covariates such as temperature, rainfall, and vegetation density, that go into the model and help predict malaria.

Professor Gething said more data meant more answers for exactly where to allocate budget and resources – right down to individual provinces.

“While these interventions aren’t rolled out in a reactive, responsive way, they do help the next several years of planning with a purpose for aiming to manage malaria better in the future,” he said