The Quality of Life Inventory-Disability (QI-Disability) is a parent reported outcome assessment of quality of life for children and adolescents with intellectual disability. It is suitable to use for children and adolescents aged 3 to 18 years and with adults who live with severe disability conditions.

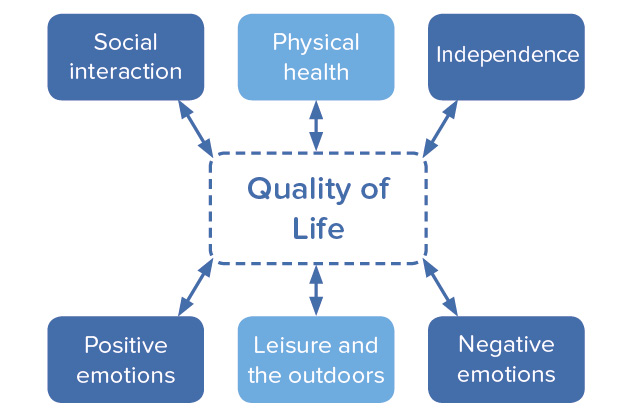

There are 32 items in six domains, including Physical Health, Positive Emotions, Negative Emotions, Social Interactions, Leisure and the Outdoors, and Independence.

All items are presented in plain language – their development was based on “think aloud” interviews with parents. Parents rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the frequency they have observed the behaviour in the child.

QI-Disability has been translated into other languages, including Spanish (US), Spanish (Spain), Spanish (US) French, Italian, German and Danish.

Contact Jenny.Downs@telethonkids.org.au to find out how QI-Disabilty can be accessed.

Where and why is QI-Disability used?

We were driven to develop QI-Disability because of family-directed priorities. During our consultations, consumers have told us that “Quality of life is not a soft outcome, but it is a hard outcome. Quality of life is the most important outcome for their child – and everyone involved with the child’s care should support the child to achieve their best quality of life." Accordingly, we developed and validated QI-Disability and have enabled it to be used across multiple sectors internationally.

More than 160 requests have come from 26 countries across every continent since QI-Disability was published in 2019.

End-users work in multiple healthcare and disability settings and are incorporating QI-Disability as an outcome measure in their work. For example:

- Pharmaceutical companies are requesting use of QI-Disability as an outcome measure in their clinical trials for rare diseases. For example, NCT05025332, NCT05011851, NCT05163314.

- We recently reported on non-seizure outcome measures including quality of life measured by QI-Disability in a randomised controlled study evaluating the effect of ganaxolone, an anti-seizure medication, in the CDKL5 deficiency disorder.1 Available open access here. - QI-Disability has been used as an outcome measure to evaluate inclusive community programs for children with high and complex needs. For example,

- Evaluating “Experience Collider”, an inclusive circus program for adolescents with complex and high needs. Click here for a description of the program and click here for the evaluation report.

- Evaluating the effects of “SPARKLE”, a community program that supported leisure activities in the real world for children and adolescents with complex needs. See here. - QI-Disability is part of the battery of clinical outcome assessment in internation rare disease registries including Simons Searchlight, RAREX and the International Rett Syndrome Foundation.

- For example, click here - Medical and allied health professionals internationally are using QI-Disability in their research and clinical work.

- Examples include hospital departments that have incorporated QI-Disability in their electronic medical records systems and therapists in behavioural support settings who are using QI-Disability domain scores to guide the planning of interventions. - Parents have contacted us to use QI-Disability for planning their child’s daily schedules to optimise quality of life.

- In the words of a mother of a young person with Rett syndrome:

“As I reflect across the domains of the Quality of Life Framework for QI-Disability, I note that her priorities change from time to time depending on her individual needs, but as a checklist for the management of her condition and her life, the framework acts as a valuable guide for me, our family and her carers.”

How to administer QI-Disability

Modes of administration

QI-Disability has been validated as an online assessment. It is user-friendly, uncluttered and to the point. Smaller numbers of parents have completed QI-Disability on paper or during a clinical interview.

The questionnaire takes about 10 minutes to complete.

Providing responses

The respondent is asked to reflect on their observations of the child during the past 1 month (30 days) when rating each of the items, a commonly used time frame for questionnaire measures.

The respondent is asked to rate each item as an average over the past 1 month (30 days). Many children will experience variability in their behaviours and activities and respondents are asked to give a rating that captures the average for the 30-day period.

There are no right or wrong answers. The respondent is asked to provide their best answers for the child over the last month. For each question, the respondent is asked to reflect on their observations of the child's well-being and enjoyment of life over the past month. The assessment asks about what the respondent has observed, not what the respondent feels or what the respondent thinks that the child may feel.

How to explain QI-Disability to parent caregivers prior to their rating of items

Explain that:

- The questions are about the child's life over the past 1 month (30 days). We would like to know how the parent/caregiver observes the child respond to a range of life experiences.

- There are no right or wrong answers – the parent/caregiver is asked to provide their best answers for the child.

- For each question, the parent/caregiver reflects on their observations of the child's well-being and enjoyment of life.

- Each question has five response options: “never, rarely, sometimes, often, very often”. The parent caregiver is asked to select the option that best applies to the child.

- If they have any questions, to please let the administrator know.

Scoring

No item is not applicable. Respondents are encouraged to answer all items. There are rules for managing missing data – see Jacoby P, Whitehouse A, Leonard H, et al. Devising a Missing Data Rule for a Quality of Life Questionnaire-A Simulation Study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2022;43:e414-e418..2

The items in the Negative Emotions score are reverse scored.

Each item is transformed to a 100-point scale. Items for a domain are averaged to give a domain score. Domain scores are averaged to give the total score.

Contact Jenny.Downs@telethonkids.org.au for information about scoring.

How did we develop QI-Disability?

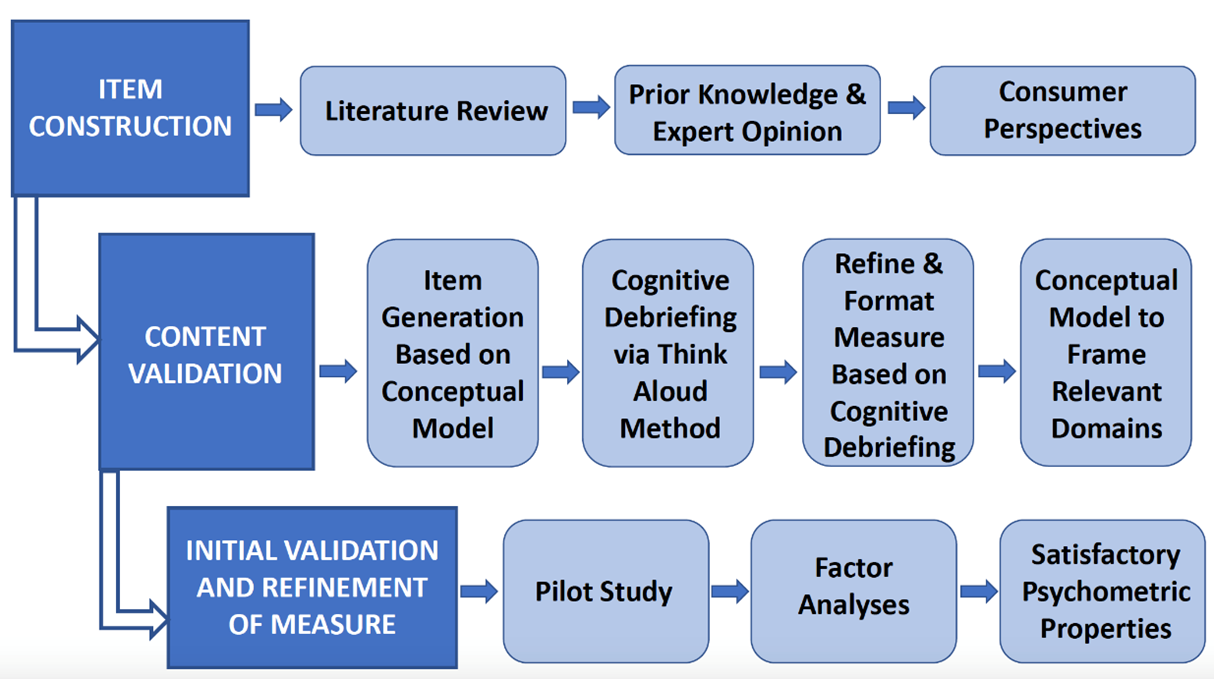

QI-Disability was designed by Australian researchers in direct collaboration with the families and carers of individuals across the spectrum of intellectual disability. This section presents a figure showing a summary of the methodologies for developing QI-Disability and a narrative describing the research we have conducted using QI-Disability.

Development Process

We undertook four qualitative studies to investigate the domains of quality of life (QOL) important to children with intellectual disability. In-depth interviews were conducted with parents of five to 18-year-old children with either Down syndrome (n=17), Rett syndrome (n=21; a severe genetic neurodevelopmental disorder mainly affecting females), cerebral palsy (n=18) or ASD (n=21).3-6 Together these conditions represented a range of characteristics seen in the broader population of those with intellectual disability including functional, behaviour and socialization difficulties; medical comorbidities; and different needs for autonomy. QOL domains were consistent across the four groups and included physical health and emotional wellbeing; pleasure in communication, movement, and day-to-day routines; and satisfaction derived from social connectedness, leisure activities and the natural environment. These data were consistent conceptually with the ICF.7 We found subsequently that the 6 domains of QOL were consistent for children with the CDKL5 deficiency disorder8 and for adults with Rett syndrome9 and the CDKL5 deficiency disorder.8

Content validation

Questionnaire items were extracted from the 77 parent caregiver interview data. A draft of QI-Disability was administered to 16 parent caregivers with a child with intellectual disability. Parents participated in a cognitive interviewing procedure known as the “think-aloud” method. After reviewing all think-aloud interview data, 41 of the 50 items remained in the draft measure: six of the original items were excluded because they did not capture the intended meaning of the item, and three items were combined with other closely related items to avoid repetition. The wording of 24 (48%) items was revised to align with parent interpretations. This development process provided evidence for the content validity of QI-Disability because ongoing consumer feedback shaped the extraction of items from the qualitative dataset.10

Psychometric validation

Initial validation:

QI-Disability was administered to 253 primary caregivers of children (aged 5-18 years) with intellectual disability across four diagnostic groups: Rett syndrome, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, or autism spectrum disorder.11

- Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses: Six domains were identified: physical health, positive emotions, negative emotions, social interaction, leisure and the outdoors, and independence.

- Goodness of fit of the factor structure: Goodness of fit statistics were satisfactory and similar for the whole sample and when the sample was split by ability to walk or talk. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.72 for “physical health” to 0.90 for “positive emotions”.

- Comparison of diagnostic groups: On 100-point scales and compared to Rett syndrome, children with Down syndrome had higher leisure and the outdoors (coefficient 10.6, 95%CI 3.4,17.8) and independence (coefficient 29.7, 95%CI 22.9, 36.5) scores whereas children with autism spectrum disorder had lower social interaction scores (coefficient -12.8, 95%CI -19.3, -6.4). Scores for positive emotions (coefficient -6.1, 95%CI -10.7, -1.6) and leisure and the outdoors (coefficient 5.4, 95%CI -10.6, -0.1) were lower for adolescents compared with children.

Test–retest reliability and responsiveness:

QI-Disability was administered twice over a one-month period to a sample of 55 primary caregivers of children (aged 5-19) with intellectual disability. Caregivers also reported their child’s physical and mental health and completed a four-item Perceived Stress Scale to assess parental stress.12

- After accounting for changes in child health and parental stress, adjusted ICC values showed substantial agreement for the total QI-Disability score and four domain scores (adjusted ICC≥0.80). Adjusted ICC scores indicated moderate agreement for the Physical Health domain (adjusted ICC=0.68) and fair agreement for the Positive Emotions domain (adjusted ICC=0.58).

- The minimal detectable difference for the total score was 4.83 out of 100, indicating the change that is greater than within subject variability.

- Improvements in a child’s physical health rating were associated with higher total, Physical Health and Positive Emotion domain scores, while improvements in mental health were associated with higher total and Negative Emotions domain scores indicating better quality of life. This indicates satisfactory test-retest reliability and preliminary evidence of its responsiveness to changes in child health.12

Known groups validation:

The predictors of QOL have been investigated in three studies. Findings are consistent with theory and provide further evidence of the validation of QI-Disability.

- Children who are fully dependent on others for their personal needs and those who find it difficult to make eye contact when speaking have lower QOL scores. More frequent participation in the community was associated with higher QOL scores, irrespective of the level of functional ability.13

- Comorbidities also influence the child’s QOL, particularly the presence of recurrent pain, insomnia and excessive daytime somnolence are associated with poor QOL scores.14

- Rett syndrome - Children with the Arg294* mutation had low QOL scores, driven by difficulties with sleep and behaviour.15

We have developed guidelines for how to manage missing data.2 We have reported the parent psychological distress does not have a mediating or moderating effect on the relationship between functional abilities and QOL as measured by QI-Disability.16 We have used QI-Disability in analyses for the CDKL5 deficiency disorder.17-20 The domain framework has informed interpretation of psychometric evaluation of qualitative data on child experiences following gastrostomy,21 the EQ-5D-Y when used for children with intellectual disability22,23 and meaningful change in SCN2A-DEE.24 See the reference list below.

References

- Downs J, Jacoby P, Specchio N, Cross H, Amin S, Bahi-Buisson N, Rajaraman R, Suter B, Devinsky O, Aimetti A, Busse G, Olson HE, Demarest S, Benke TA, Pestana-Knight E. Effects of ganaxolone on non-seizure outcomes in cdkl5 deficiency disorder: Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2024; 51: 140-6.

- Jacoby P, Whitehouse A, Leonard H, Saldaris J, Demarest S, Benke T, Downs J. Devising a missing data rule for a quality of life questionnaire-a simulation study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2022; 43(6): e414-e8.

- Davis E, Reddihough D, Murphy N, Epstein A, Reid SM, Whitehouse A, Williams K, Leonard H, Downs J. Exploring quality of life of children with cerebral palsy and intellectual disability: What are the important domains of life? Child Care Health Dev 2017; 43(6): 854-60.

- Epstein A, Leonard H, Davis E, Williams K, Reddihough D, Murphy N, Whitehouse A, Downs J. Conceptualizing a quality of life framework for girls with rett syndrome using qualitative methods. Am J Med Genet A 2016; 170A: 645-53.

- Epstein A, Whitehouse A, Williams K, Murphy N, Leonard H, Davis E, Reddihough D, Downs J. Parent-observed thematic data on quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorder Autism 2019; 23(1): 71-80.

- Murphy N, Epstein A, Leonard H, Davis E, Reddihough D, Whitehouse A, Jacoby P, Bourke J, Williams K, Downs J. Qualitative analysis of parental observations on quality of life in australian children with down syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 2017; 38(2): 161-8.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health: Icf. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2001.

- Tangarorang J, Leonard H, Epstein A, Downs J. A framework for understanding quality of life domains in individuals with the cdkl5 deficiency disorder. Am J Med Genet A 2019; 179(2): 249-56.

- Strugnell A, Leonard H, Epstein A, Downs J. Using directed-content analysis to identify a framework for understanding quality of life in adults with rett syndrome. Disability and Rehabilitation 2020; 42(26): 3800-7.

- Epstein A, Williams K, Reddihough D, Murphy N, Leonard H, Whitehouse A, Jacoby P, Downs J. Content validation of the quality of life inventory-disability. Child Care Health Dev 2019; 45(5): 654-9.

- Downs J, Jacoby P, Leonard H, Epstein A, Murphy N, Davis E, Reddihough D, Whitehouse A, Williams K. Psychometric properties of the quality of life inventory-disability (qi-disability) measure. Qual Life Res 2019; 28(3): 783-94.

- Jacoby P, Epstein A, Kim R, Murphy N, Leonard H, Williams K, Reddihough D, Whitehouse A, Downs J. Reliability of the quality of life inventory-disability (qi-disability) measure in children with intellectual disability. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 2020; 41(7): 534-9.

- Williams K, Jacoby P, Whitehouse A, Kim R, Epstein A, Murphy N, Reid S, Leonard H, Reddihough D, Downs J. Functioning, participation and quality of life in children with intellectual disability: An observational study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 2021; 63: 89-96.

- Reddihough D, Leonard H, Jacoby P, Kim R, Epstein A, Murphy N, Reid S, Whitehouse A, Williams K, Downs J. Comorbidities and quality of life in children with intellectual disability. Child: Care, Health and Development 2021; n/a.

- Mendoza J, Downs J, Wong K, Leonard H. Determinants of quality of life in rett syndrome: New findings on associations with genotype. J Med Genet 2021; 58(9): 637-44.

- Whitehouse A, Jacoby P, Reddihough D, Leonard H, Williams K, Downs J. The effect of functioning on quality of life inventory-disability measured quality of life in children with intellectual disability is not mediated or moderated by parental psychological distress. Quality of Life Research 2021; 30: 2875-85.

- Downs J, Jacoby P, Saldaris J, Leonard H, Benke T, Marsh E, Demarest S. Negative impact of insomnia and daytime sleepiness on quality of life in individuals with the cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 deficiency disorder. J Sleep Res 2022: e13600.

- Saldaris JM, Jacoby P, Leonard H, Benke TA, Demarest S, Marsh ED, Downs J. Psychometric properties of qi-disability in cdkl5 deficiency disorder: Establishing readiness for clinical trials. Epilepsy Behav 2023; 139: 109069.

- Leonard H, Junaid M, Wong K, Aimetti AA, Pestana Knight E, Downs J. Influences on the trajectory and subsequent outcomes in cdkl5 deficiency disorder. Epilepsia 2022; 63(2): 352-63.

- Leonard H, Junaid M, Wong K, Demarest S, Downs J. Exploring quality of life in individuals with a severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, cdkl5 deficiency disorder. Epilepsy Research 2021; 169: 106521.

- Glasson EJ, Forbes D, Ravikumara M, Nagarajan L, Wilson A, Jacoby P, Wong K, Leonard H, Downs J. Gastrostomy and quality of life in children with intellectual disability: A qualitative study. Arch Dis Child 2020; 105(10): 969-74.

- Blackmore AM, Mulhern B, Norman R, Reddihough D, Choong CS, Jacoby P, Downs J. How well does the eq-5d-y-5l describe children with intellectual disability?: "There's a lot more to my child than that she can't wash or dress herself.". Value Health 2024; 27(2): 190-8.

- Downs J, Norman R, Mulhern B, Jacoby P, Reddihough D, Choong CS, Finlay-Jones A, Blackmore AM. Psychometric properties of the eq-5d-y-5l for children with intellectual disability. Value Health 2024; 27(6): 776-83.

- Downs J, Ludwig NN, Wojnaroski M, Keeley J, Schust Myers L, Chapman CAT, Hecker J, Conecker G, Berg AT. What does better look like in individuals with severe neurodevelopmental impairments? A qualitative descriptive study on scn2a-related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Qual Life Res 2024; 33(2): 519-28.

Acknowledgements and Contacts

We sincerely thank the families for their participation in this study. The development of the Quality of Life Inventory-Disability (QI-Disability) was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council - NHMRC. The initial series of studies took place from 2014 to 2019. Collaborators included the The Kids Research Institute Australia Perth, and the Royal Children’s Hospital, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and Monash University Melbourne.

Contact Information

For further information about QI-Disability, please contact:

Professor Jenny Downs, Senior Principal Research Fellow

Email: Jenny.Downs@telethonkids.org.au

Copyright

The QI-Disability is copyrighted to The Kids Research Institute Australia.

Citation

When publishing research using QI-Disability, please cite the following:

Downs, J., Jacoby, P., Leonard, H., Epstein, A., Murphy, N., Davis, E., Reddihough, D., Whitehouse, A., & Williams, K. 2018. Psychometric properties of the Quality of Life Inventory-Disability (QI-Disability) measure. Quality of Life Research, 28, 783-94.

Research partners

The Kids Research Institute Australia

The University of Western Australia

Murdoch Children’s Research Institute