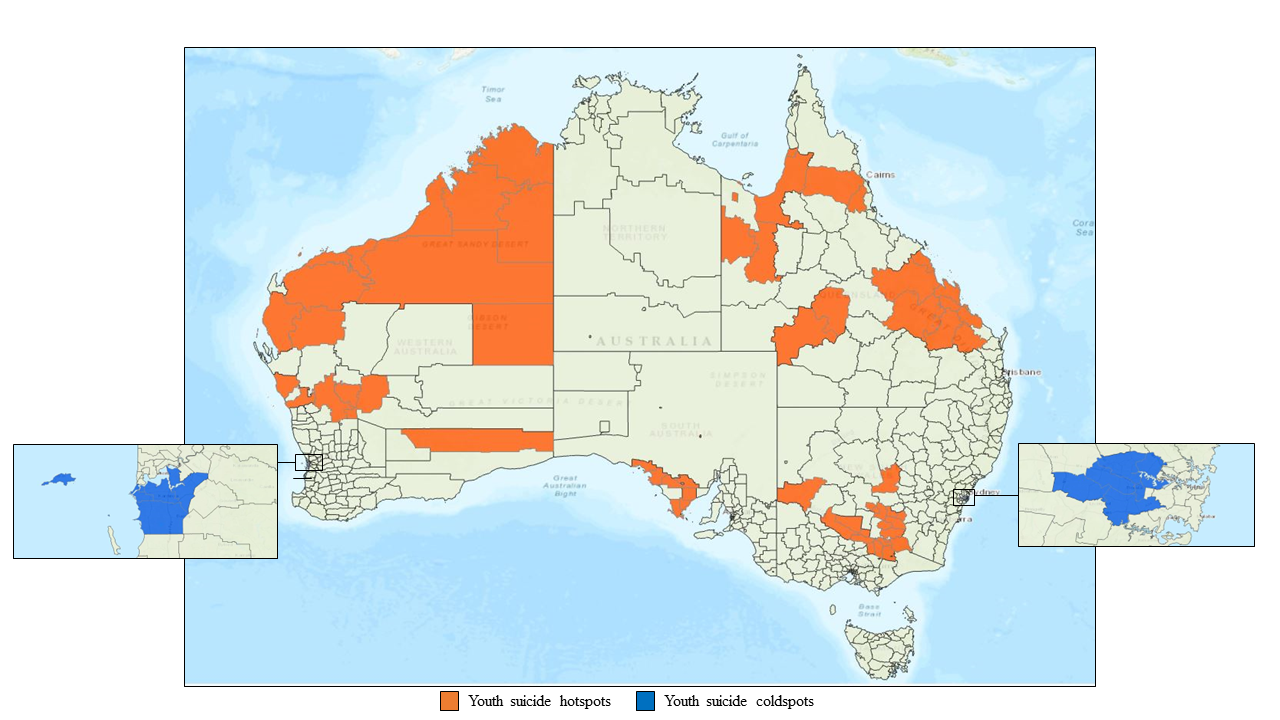

Image: Youth suicide hotspots (in orange) and coldspots (in blue) identified as part of the study

Communities with poor access to mental health services are eight times more likely to be youth suicide hotspots, according to new The Kids Research Institute Australia research.

In a paper published today in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, researchers used national coronial data to map suicides of 1,959 young people aged 10-24 who died between 2016-2020.

Led by suicide prevention researcher Dr Nicole Hill, the team identified eight suicide ‘hotspots’ where there were significantly more suicides than would be expected, and two ‘coldspots’ where rates of suicide were far lower.

Large swathes of remote and regional Western Australia and Queensland, as well as parts of country New South Wales and South Australia, were identified as particular hotspots for youth suicide, while areas of metropolitan Perth and metropolitan Sydney were identified as coldspots.

The team compared the characteristics of communities in these contrasting areas, including the number of mental health services and mental health staff available, opening times, and travel time to services at the time young people were in a state of acute suicidal crisis and died by suicide.

“This technique considered not just the number of services but how accessible they were to young people at the time of their death,” Dr Hill said.

The findings showed that hotspot communities had substantially lower access to mental health services compared to coldspot communities.

“Specifically, we found areas with low mental health workforce supply were associated with eightfold greater odds of a suicide occurring in a hotspot compared to non-cluster suicides,” Dr Hill said.

“The suicide coldspots we identified all occurred in areas characterised by moderate-to-high mental health workforce supply.”

In addition to access to mental health services, illicit substance use among young people at their time of death was 20 per cent higher in hotspot communities.

“It’s a known problem that people who have substance misuse problems are often not eligible to access mental health services. This is a real missed opportunity for youth suicide prevention and the prevention of suicide clusters,” Dr Hill said.

By comparing hotspots with coldspots the researchers were able to not only establish the link between higher suicide rates and lower access to services, but that high access to mental health services may be a protective factor against suicide in young people.

“These findings have important implications for postvention and the prevention of suicide contagion, where a cluster of suicides can follow the suicide of someone within a community,” Dr Hill said.

When a young person dies by suicide, there is often a lot of fear and anxiety about the prospect of further deaths in the community. This research suggests that providing timely access to mental health services, particularly in the aftermath of a suicide, may potentially be protective against further deaths.

Dr Hill said the paper represented the first controlled study where researchers had been able to show a strong link between service access and higher or lower suicide rates.

“It’s really the first time we have been able to identify a modifiable risk factor because we can’t make a community less remote, but we can improve access to services in that community,” she said.

“It’s an empowering message: there is something we can actually do about it.

“It also points to an important message around postvention and the prevention of suicide clusters, that in the aftermath of suicide the community should assess factors that may impact help-seeking – such as current waitlist times to mental health services – because if those supports aren’t in place there could be the risk of further deaths.

“We can’t just be telling people to seek help when a suicide occurs, because if that help isn’t available we are potentially increasing helplessness and putting that community at greater risk.”

Dr Hill said the findings also highlighted the risks associated with rapid development, where there can be a significant lag in health infrastructure and mental health support services.

“WA has the nation’s highest population growth following COVID-19. This paper shows that we need to have mental health services scaled up to accommodate the increased demand for services.”

The full paper, Association between mental health workforce supply and clusters of high and low rates of youth suicide: An Australian study using suicide mortality data from 2016 to 2020, can be read here.

Dr Hill is Senior Research Fellow in Suicide Prevention at The Kids Research Institute Australia and a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Fellow, with additional support from Mineral Resources.

This study was a collaboration between The Kids Research Institute Australia, the University of Melbourne and the Curtin School of Population Health.

FAST FACTS

- Globally, about 800,000 people die by suicide every year

- Risk of suicide increases markedly during middle to late adolescence

- Suicide is among the top five leading causes of death in people under the age of 25, globally, and the leading cause of preventable deaths in young Australians aged 10-24 years