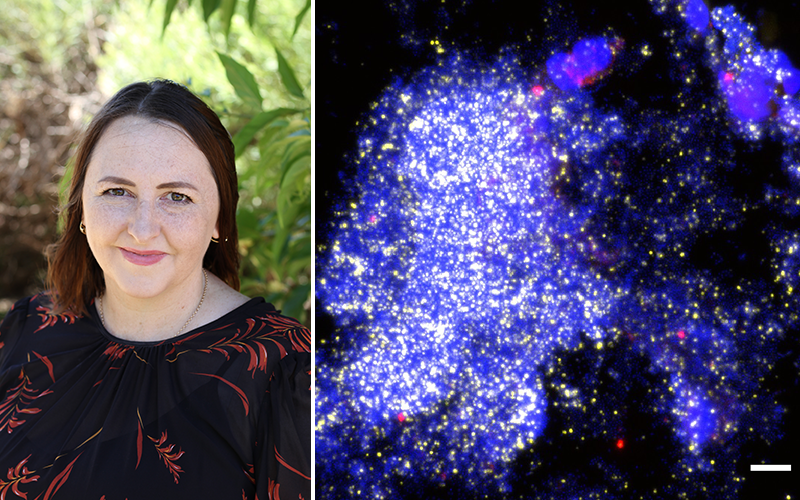

Pictured (left) Dr Ruth Thornton and (right) microscopy pictures of a large biofilm in fluid collected from the lung of a child with protracted bacterial bronchitis. The blue areas show the child’s immune cells and DNA, while the other colours show the different kinds of bacteria living in their lungs. CREDIT: The Kids Research Institute Australia.

The Kids Research Institute Australia and Menzies School of Health Research researchers using powerful microscopes have identified bacterial slime in the lungs of some children with persistent wet coughs – a breakthrough which could help explain why some children experience recurrent chest infections which aren’t fixed by antibiotics.

Many children experience a prolonged wet cough after having an acute cough and can develop a condition called protracted bacterial bronchitis (PBB). Children with recurrent PBB are, in turn, at increased risk of progressing to a severe lung disease called bronchiectasis.

In a collaborative study published in prestigious journal, The Lancet Microbe, researchers from The Kids Research Institute Australia, Menzies School of Health Research (Menzies), and The University of Western Australia (UWA) studied samples taken from 144 children with persistent wet coughs to see if they could find evidence of bacterial slime – called a biofilm – in their lungs.

Such biofilms are hypothesised to contribute to poor treatment outcomes among children with chronic lung disease, but data on this are scarce. For the first time, the researchers were able to demonstrate – and record – biofilms in the lungs of some of the children.

The researchers used a process known as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) to collect a sample from the lungs for testing. During the procedure, a sterile solution is used to flush the child’s airways and capture a fluid sample containing the germs that cause the child’s chest infection.

Senior author and Research Fellow with The Kids Research Institute Australia and UWA, Dr Ruth Thornton – whose team then examined the samples at The Kids – said that using the powerful microscope with contrasting colours assisted in locating and identifying the bacterial slime present in the affected lungs.

“This is an important discovery, as we know that when bacteria live in these slimes they can be more than a thousand times more resistant to antibiotics than the bacteria that cause the acute infections that you take your child to the doctor for,” Dr Thornton said.

"This means that when you stop antibiotics your child is likely to get yet another infection."

Lead author, Menzies Senior Research Fellow Dr Robyn Marsh, said that for most children with PBB, their cough would get better after having a two-week course of antibiotics.

“But we also know that some kids will have repeated episodes of bronchitis that never seem to get better,” Dr Marsh said.

This puts them at risk of developing a severe lung disease called bronchiectasis. We know that chest infections can lead to PBB and bronchiectasis, but the reason why only some kids respond to antibiotics isn’t always clear.

Menzies Head of Child Health Professor Anne Chang AM described the study results as an exciting way forward to help treat children who had been suffering.

“This is really exciting. We’ve suspected these children have biofilm-associated infections for a while but until now, no one has proven it. Now that we’ve seen it, we can start investigating new ways to treat these children so that fewer of them will progress to having severe lung disease,” Professor Chang said.

The full paper – Prevalence and subtyping of biofilms present in bronchoalveolar lavage from children with protracted bacterial bronchitis or non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a cross-sectional study – can be read in The Lancet Microbe.

The study was funded grants from the Financial Markets for Children and NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence for bronchiectasis in children (AusBREATHE).